What Percent of Women Have a Baby in the Usa

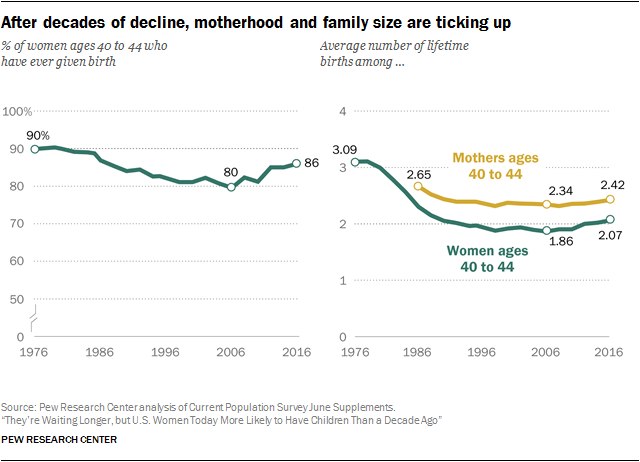

The share of U.S. women at the cease of their childbearing years who have ever given nativity was college in 2016 than it had been x years before. Some 86% of women ages twoscore to 44 are mothers, compared with fourscore% in 2006, co-ordinate to a Pew Enquiry Middle assay of U.S. Demography Bureau data.i The share of women in this age group who are mothers is similar to what information technology was in the early 1990s.

Not only are women more likely to be mothers than in the by, merely they are having more children. Overall, women have ii.07 children during their lives on average – up from 1.86 in 2006, the everyman number on record. And amidst those who are mothers, family size has also ticked upwards. In 2016, mothers at the cease of their childbearing years had had about two.42 children, compared with a low of 2.31 in 2008.

The contempo ascent in motherhood and fertility might seem to run counter to the notion that the U.Due south. is experiencing a mail-recession "Baby Bust." Notwithstanding, each tendency is based on a different type of measurement. The analysis here is based on a cumulative measure of lifetime fertility, the number of births a adult female has ever had; concurrently, reports of failing U.Due south. fertility are based on almanac rates, which capture fertility at one point in time.2

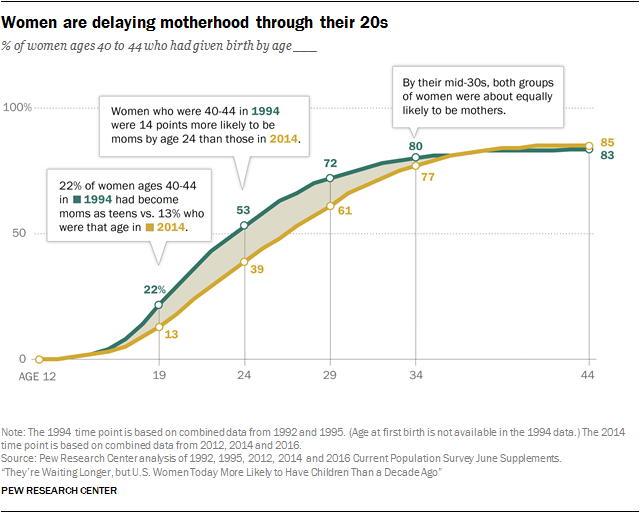

I cistron driving downwardly annual fertility rates is that women are condign mothers later in life: The median historic period at which women become mothers in the U.S. is 26, compared with 23 in 1994. This change has been driven in function past declines in births to teens. In the mid-1990s, near one-in-5 women in their early on 40s (22%) had had a child prior to age xx; in 2014, that share had dropped to thirteen%. And delays in childbearing have connected amidst women in their 20s: While slightly more than half (53%) of women in their early on 40s in 1994 had become mothers by age 24, this share was 39% among those who were in this historic period grouping in 2014.

The Great Recession intensified this shift toward later motherhood, which has been driven in the longer term by increases in educational attainment and women's labor forcefulness participation, equally well as delays in wedlock. Given these social and cultural shifts, it seems likely that the postponement of childbearing will continue. But will the recent almanac declines in fertility atomic number 82 U.S. women to have smaller families in the futurity? It is difficult to know, but comparing the lifetime fertility of women who just recently completed their childbearing years with those 20 years earlier suggests that postponing births does not necessarily equate with lower lifetime fertility.

The majority of women ages 40 to 44 who have never married have had a baby

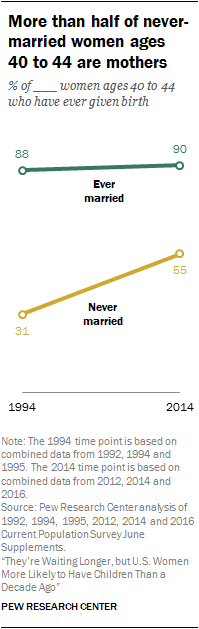

There has been a substantial increment in motherhood over the past two decades among women who have never married. As in the U.South. population every bit a whole, the share of women at the end of their childbearing years who have never wed has risen – from 9% in 1994 to 15% in 2014. Among these women, a majority (55%) have had at least one child. This marks a dramatic change from two decades earlier, when roughly a third (31%) of never-married women in their early on 40s had given nascence.three At the aforementioned fourth dimension, the share of women who become mothers among those who have been married remains high: 90% in 2014, compared with 88% in 1994.4

The upward trend in the share of never-married women having children is particularly striking given the overall falloff in births to teens in recent decades. While there has been an uptick in the share of never-married women in their early 40s who became mothers during their teenage years (from 11% to 15%), nigh of the growth in motherhood occurred at slightly older ages. For case, past historic period 29, 45% of never-married women in their early on 40s in 2014 were moms, compared with 26% of their counterparts in 1994.

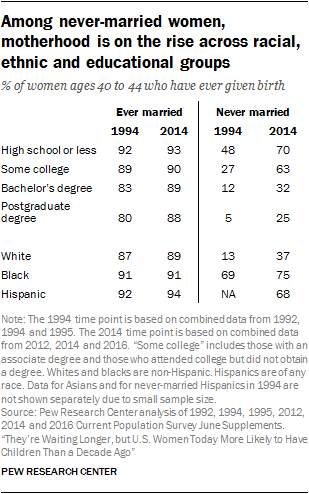

The share of never-married women in their early 40s who are mothers has risen across all educational levels equally well. In fact, rates of motherhood accept more than doubled for never-married women with some college feel equally well as those with a bachelor'south caste or more education. For case, childlessness was almost universal among never-married women in their early 40s with a postgraduate degree in 1994, while in 2014 ane-in-four comparable never-married women had a child. Still, despite the rapid gains in motherhood among never-married women with at least a bachelor's degree, those with a high school diploma or less instruction remain more likely to be mothers: seventy% are.

Maternity rates have risen dramatically among white never-married women in their early 40s. In 2014, 37% were mothers, compared with just 13% two decades ago. Rates as well ticked up amongst their blackness counterparts: 75% were mothers in 2014, compared with 69% in 1994.

Amongst women in their early 40s who have been married, the share that has given birth also has risen for those with a available's (from 83% to 89%) or postgraduate degree (from 80% to 88%). There has been no notable change in the share of e'er-married women with less education who are mothers.

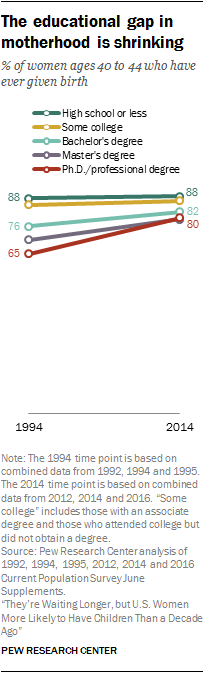

Biggest increases in motherhood amid women with postgraduate degrees; shifts in timing evident across all educational groups

The share of all women ages xl to 44 without a bachelor'south degree who are mothers has held steady over the past 2 decades while increasing amongst those with more education. As of 2014, 82% of women at the stop of their childbearing years with a bachelor's degree were mothers, compared with 76% of their counterparts in 1994. And while 79% of women in their early 40s who have a primary'southward degree also take at least one child, this share was 71% twenty years before. The about dramatic increase in motherhood has occurred amidst the relatively small group of women in their early 40s with a Ph.D. or professional person caste, eighty% of whom are mothers; amidst their predecessors, simply 65% were.

The share of all women ages xl to 44 without a bachelor'south degree who are mothers has held steady over the past 2 decades while increasing amongst those with more education. As of 2014, 82% of women at the stop of their childbearing years with a bachelor's degree were mothers, compared with 76% of their counterparts in 1994. And while 79% of women in their early 40s who have a primary'southward degree also take at least one child, this share was 71% twenty years before. The about dramatic increase in motherhood has occurred amidst the relatively small group of women in their early 40s with a Ph.D. or professional person caste, eighty% of whom are mothers; amidst their predecessors, simply 65% were.

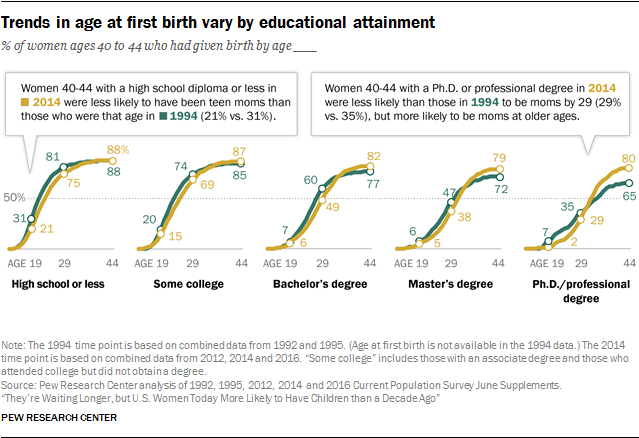

Across all levels of educational attainment, the timing of motherhood has shifted as a outcome of declines in showtime births to those in their teens, or to those in their early 20s.

Amidst women at the end of their childbearing years with a high school diploma or less education, 21% became mothers in their teens, 56% had done so by the fourth dimension they were 24 and 75% were mothers past age 29. Among their counterparts in 1994, 31% had given birth prior to age 20, two-thirds had done so past historic period 24 and 81% were mothers by 29. Similarly, smaller shares of women in 2014 who were at the end of their childbearing years and had some higher instruction had become mothers before historic period twenty (15%) than was the instance in the mid-1990s, when the share stood at 20%. This filibuster in motherhood was more prominent past age 24 (45% vs. 56% in 1994) and had narrowed by age 29 (69% vs. 74%).

Women at the end of their childbearing years who take a higher degree are also delaying motherhood well into their 20s. In 2014, about half (49%) of women in their early on 40s with a bachelor'southward degree had given nativity by historic period 29, compared with 60% of their counterparts in 1994. By age 34, however, women who are at the cease of their childbearing years had "caught upwards" to their predecessors: 72% of each grouping had get mothers by that age.

A somewhat different pattern emerges among women with advanced degrees who are at the end of their childbearing years. While they, too, were less likely to become mothers by the cease of their 20s than their counterparts in 1994, in their 30s they became notably more probable to be moms than their predecessors. In 2014, 38% of women ages 40 to 44 with a principal's caste had become mothers by age 29 and 77% had become moms past 39. In comparison, 47% of women 40 to 44 in 1994 were mothers by age 29, and 71% were moms past the finish of their 30s. And although at historic period 29 comparable women with a Ph.D. or professional person degree were however less probable than their counterparts in 1994 to have had a baby (29% vs. 35%), by age 34 they were more probable to take done and then (61% vs. 50%).

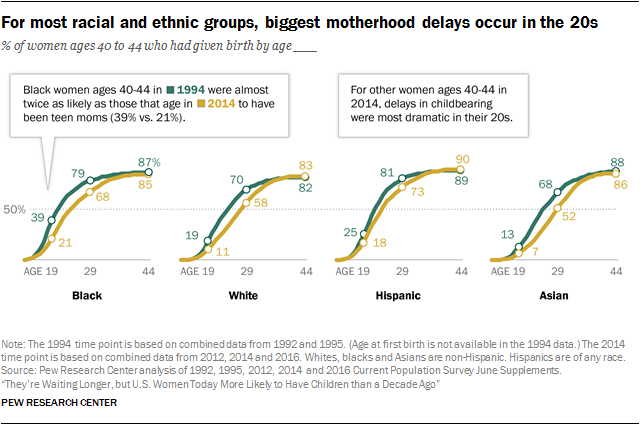

Women of all races and ethnicities delaying maternity

Amongst women who recently reached the end of their childbearing years, Hispanics are the most likely to have ever given birth: xc% have washed so, compared with 85% of black women, 86% of Asian women and 83% of white women. This pattern is similar to that of women at the cease of their childbearing years in the mid-1990s.

While there has been lilliputian modify in recent decades in the shares of women who are mothers across racial and ethnic groups, the historic period at which women are becoming mothers has risen across all groups.

Amidst black women who recently finished their childbearing years, virtually all of the delay in motherhood originated in declines in teen motherhood. Some 21% of black women in their early 40s in 2014 had had a baby in their teens – a effigy merely over half that of their counterparts in 1994 (39%). To a lesser extent, the postponement in births that began in the teen years persisted at older ages: 68% had become mothers by the stop of their 20s, compared with 79% among black women in their early 40s in 1994.

Amongst women in other racial and indigenous groups who were at the cease of their childbearing years in 2014, the delays in motherhood were more pronounced in their 20s. A third of white women ages forty to 44 had become mothers by age 24 and 58% had done and then by age 29. Among their counterparts in 1994, half were moms by age 24, and 70% had given nascence by age 29. Among Hispanic women, 53% of those who were in their early on 40s in 2014 had become mothers by historic period 24 and 73% were moms by age 29. In comparison, 65% of their counterparts in 1994 were moms by 24 and 81% had given nascency by the end of their 20s. Meanwhile, a quarter of Asian women who were in their early on 40s in 2014 had become mothers past age 24 and 52% were mothers by the end of their 20s; in 1994, 43% were mothers by age 24, and 68% were mothers by historic period 29.

Nigh the data

This written report is based primarily on information from the U.S. Census Bureau'due south June Supplement of the Electric current Population Survey, which produces a nationally representative sample of the not-institutionalized population of the U.South. The June Fertility Supplement was get-go administered in 1976 and is typically conducted every other twelvemonth. Public-utilize information files prior to 1986 are not readily available, so analyses of pre-1986 time points are fatigued from Census Bureau tabulations.

The bulk of analyses in this report begin in the mid-1990s, because that is when the Census Bureau first began collecting detailed information on educational attainment.

Analyses looking at all women ages 40-44, or at all mothers ages twoscore-44, are based on data from single years. For detailed analyses by historic period at get-go nativity, race and ethnicity, educational attainment and marital status, multiple years of data are combined to create sufficient sample sizes. Data from 1992, 1994 and 1995 are combined and referred to as "1994" for about of these analyses, and information from 2012, 2014 and 2016 are combined and referred to as "2014." (Data from 1992 and 1995 are combined and referred to as "1994" for analyses related to age at offset birth, since age at first birth was non collected in the 1994 survey.)

Fifty-fifty with combining years, there are some cases where sample sizes for some demographic groups were beneath 200, in which example results are not shown.

A working paper suggests that prior to 2012, when new editing protocols were implemented past the Demography Bureau, the Current Population Survey may have overestimated childlessness somewhat. This makes it difficult to decide the exact magnitude of changes in childlessness beyond fourth dimension, though simulations suggest that childlessness at present is lower than it was around 10 years ago, and no college than information technology was around the early 1990s, even taking the new editing protocol into account.

The phrases "in their early 40s," "at the end of their childbearing years" and "ages 40 to 44" are used interchangeably to describe women in this report. Defining the end of the childbearing years as ages 40 to 44 has typically been the convention. This is partly due to the fact that few women have babies across these ages, and partly due to the fact that until recently, data on the completed fertility of women ages 45 and older were not typically collected. While technology is extending the age at which women can give birth, the vast bulk still have children before age 45. In 2015, near 0.2% of kickoff births occurred to women ages 45 or older, and Census Bureau estimates advise that the share of women ages xl to 44 who are childless does not differ from the share ages 44 to 50 who are childless.

The information used in these analyses are designed to assess women's fertility, and as such a "mother" is here divers as any adult female who has given birth. However, many women who do not bear their own children are indeed mothers. Estimates indicate that 6% of children with a parent householder in the U.S. are living with either an adoptive parent or a stepparent.

In the analysis past educational attainment, references to people with "high school or less" include those who take a high school diploma or its equivalent, such as a General Pedagogy Development (GED) certificate. "Some college" includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a caste. References to respondents with "postgraduate" degrees include all people who take at to the lowest degree a master's degree. Respondents with a "Ph.D./professional person degree" include, for instance, those who take an M.D., a law degree or any type of doctorate caste.

References to whites, blacks and Asians include only those who are non-Hispanic and identify as only i race. Hispanics are of any race.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/01/18/theyre-waiting-longer-but-u-s-women-today-more-likely-to-have-children-than-a-decade-ago/#:~:text=As%20in%20the%20U.S.%20population,had%20at%20least%20one%20child.

0 Response to "What Percent of Women Have a Baby in the Usa"

Post a Comment